The Byzantine Empire, often known as the Eastern Roman Empire, established Byzantine architecture. Byzantium, which became Constantinople during the rule of Constantine the Great, became the new Roman capital in 330 AD. The Byzantine era lasted until the collapse of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. The early Byzantine and Roman empires did not, however, draw a clear distinction, and early Byzantine architecture can be distinguished from older Roman architecture in terms of style and structure. Modern historians invented this language to describe the medieval Roman Empire as it developed into a unique artistic and cultural entity focused on Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) rather than the city of Rome and its surroundings. Its architectural style had a significant impact on subsequent medieval construction in Europe and the Near East.

Hagia Sophia

Hagia Sophia is located in Istanbul, Marmara, Turkey. One of the most illustrious emperors of the Byzantines, Justinian the Great, oversaw the construction of the Hagia Sophia. This era is frequently regarded as the pinnacle of Byzantine history. The building’s construction took about 5 years, 10 months, which is a remarkable achievement! This is amazing, especially when you consider that far smaller churches in Europe sometimes took hundreds of years to construct a thousand years later. The church was not only built so swiftly, but when it was finished, it was also the most prominent structure on the whole planet.

Particularly notable is the Hagia Sophia’s Dome. It surpassed the dome of the Pantheon in Rome as the biggest dome in the world when it was finished. The Hagia Sophia was the leading Eastern Orthodox Church until 1453 when it was converted into a mosque by the Ottomans, who took control of Constantinople after defeating the Byzantines. The Hagia Sophia lost the title of “world’s largest dome” only after Brunelleschi’s dome at Florence Cathedral was completed. The structure underwent extensive Ottoman Turk modification, including several expansions, prayer rooms, and four sizable stone minarets.

Euphrasian Basilica

The Euphrasian Basilica is another example of Byzantine architecture from the height of the empire. The church, which was constructed during Justinian I’s time, is among the finest specimens of Byzantine architecture in all of contemporary Croatia. The church itself features a linear basilica-style floorplan, like other churches in Ravenna. Byzantine mosaics in the church’s apse are renowned for being especially spectacular. The Byzantines made several technological improvements to the art of mosaics, despite the fact that they had been utilized for thousands of years. Over the years, Byzantine mosaics have had a significant impact on a variety of different art styles.

Dome of the Rock

On the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem, there is a sanctuary called the Dome of the Rock. Abd al-Malik, the Umayyad Caliph, ordered its initial completion in 691 CE during the Second Fitna. Currently, the Dome of the Rock is among the earliest examples of Islamic construction. The “most recognizable landmark in Jerusalem” is what it has been dubbed. The Byzantine Chapel of St. Mary, which stood on the route connecting Jerusalem and Bethlehem between 451 and 458, may have had an impact on the building’s octagonal design. The rock at the center of the site, known as the Foundation Stone, is significant to Jews, Christians, and Muslims in accordance with their respective religious traditions.

Chora Church

One of the most exquisite remaining Byzantine churches is said to be Chora’s Church of the Holy Saviour. The church is located in Istanbul’s Edirnekap district, which is a part of the Fatih municipality’s western region. The church was first transformed into a mosque in the 16th century, during the Ottoman Empire, and then, in 1948, it was turned into a museum. The building’s interior is decorated with exquisite paintings and mosaics.

Monastery of the Pantocrator

The second-largest Byzantine religious structure still standing in Istanbul is the Monastery of the Pantocrator. Actually, the Monastery consists of two distinct churches and a smaller chapel. All of these structures were built utilizing brick masonry, and the mortar joints between the bricks are significantly broader than the bricks themselves. This method was often used in Byzantine architecture at this time, as seen by the numerous structures that utilize it today in Greece, Anatolia, and the Balkans. The Monastery was turned into a mosque during the Ottoman invasion of Constantinople, and it continues to be one today. The edifice is now known as the Zeyrek Mosque, and while the inside more closely resembles other mosques in Istanbul, remnants of the earlier Byzantine architecture are still visible.

Australian War Memorial

The Australian War Memorial serves as the country’s official memorial to the personnel of its armed services and affiliated groups who have lost their lives or taken part in Australian-led conflicts. There is a large national military museum at the memorial. One of the most notable monuments of its kind in the world, the Australian War Memorial was inaugurated in 1941. The Memorial is in Canberra, the capital of Australia. The ceremonial land axis of the city, which extends from Parliament House on Capital Hill down a line cutting through the peak of the cone-shaped Mount Ainslie to the northeast, has its northern endpoint here. There is no direct route connecting the two locations, however, there is a clear line of sight from Parliament House’s front balcony to the War Memorial and from the War Memorial’s front steps back to Parliament House. The Australian War Memorial is divided into three sections: the Research Center, the Galleries, and the Commemorative Area, which includes the Hall of Memory and the Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier. There is a sculpture garden outside the Memorial as well.

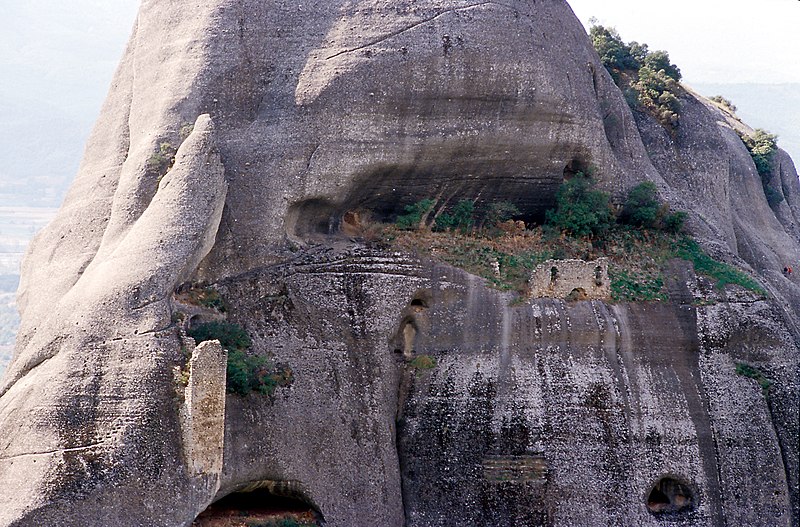

Fortifications of Trebizond

The walls, towers, gates, and bridges that made up Trebizond’s defences encircled the city’s medieval core. Since they have been altered over the years, it is practically impossible to pinpoint the precise period of their construction. A significant majority of the building was constructed during the Byzantine and Trebizond Empires, however other elements date back to the Roman era. As the Byzantine Empire was disintegrating in the late middle ages, a successor state, the Empire of Trebizond, operated independently. Trebizond was one of the major seaports on the Black Sea at the time the walls were constructed.

Sacral Byzantine Architecture

The adoption of Christianity as the Roman Empire’s official religion signaled the beginning of one of the most significant developments in the history of architecture. The first manifestation of Byzantine church architecture is a basilica with a wood roof. From the fourth to the sixth century, this style of church predominated in developing churches along the eastern Mediterranean coast.

This style of church may be seen, for instance, in Rome’s Santa Sabina, which was constructed between 422 and 432. The transition to vaulted cathedrals, which peaked with the extraordinary display of Byzantine inventiveness known as Hagia Sophia, constructed between 532 and 537, was made in the sixth century. Byzantine church architecture began to vary throughout the so-called Middle Byzantine period. The evolution of the theology of pictures following the Iconoclasm had an impact on the creation of a uniform scheme for interior design and architectural layout.

The cross-in-square church, which first appeared in the ninth century, was widely utilized for more than five centuries in Greece and Asia Minor. One of the oldest specimens may be discovered in the Hosios Loukas monastery in Greece, which was constructed between 946 and 955. No matter what kind of churches they were, the vast number that Byzantines erected demonstrates the centrality of Christianity in the 4th-century Roman state’s system of government.

Martyria & Baptisteries

A martyrium is a centrally organized building that is often erected above a Christian martyr’s tomb. Martyria were built according to no set architectural form and come in a broad range of shapes, including round, polygonal, and cross-shaped. The devout may frequently go closer to the saint’s bones by standing on a lowered floor. Constantine started the process of erecting grand structures in honor of Christians and Christian-related figures and events.

The Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, constructed in the year 324, is the first of Constantine’s magnificent martyria. The grave of the apostle Peter was located under the basilica’s central feature or ciborium. Even though these structures had a less significant impact on the evolution of Byzantine architecture, they were crucial to the growth of the cult of relics and the creation of pilgrimage places.

Baptisteries, which were created from previous Roman ecclesiastical architecture, are solely Christian structures. The baptistery, where the sacrament of baptism is administered, is typically octagonal in shape. A dome, a representation of the celestial realm, covered its roof. Additionally, the baptismal font was often octagonal, surrounded by columns, and had an ambulatory. They only serve as a representation of early Christian and Byzantine architecture, though, as several of them were completely removed by the 10th century.

Monastery of Saint John the Theologian

In the late 11th century, a group of monks received the Island of Patmos from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos. Those monks started constructing a huge walled monastery very fast. It bears the name of Saint John of Patmos, who is thought to have penned numerous biblical texts. The building’s residential quarters are totally encircled by fortified walls that tower over the village below. The Monastery of Saint John the Theologian was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999 and is still an active monastery today.

Basilica of Saint’Apollinare Nuovo

This Byzantine architecture is located in Ravenna, Emilia-Romagna, Italy which is constructed in 561 CE. When the Byzantines took control of Ravenna in 540 CE, they immediately elevated it to the status of the provincial capital of the Italian mainland. The basilica was constructed by the Ostrogoth ruler Theodoric the Great, therefore one could argue that it isn’t actually Byzantine at all. Nevertheless, Byzantine architecture had a significant impact on its design, and many of the mosaics were created by Byzantine craftsmen. The Byzantines captured Ravenna from the Ostrogoths not long after the church was finished, and they altered it in a number of ways to fit their own tastes. The layout of the church is linear, with a large central nave flanked by two parallel halls, just like an original Roman basilica. Some of the oldest and best-preserved Byzantine mosaics are found throughout the cathedral. They feature famous Ravenna locations as well as numerous biblical scenarios.

Castle of Mytilene

On the Greek Island of Lesbos in the Aegean Sea stands the medieval castle known as the Castle of Mytilene. The history of the castle is intricate, with walls and towers added in the sixth century by Justinian I, the fourteenth century by John V, and the seventeenth and eighteenth century by the Ottoman Empire. The strongest stronghold on the entire island is the coastal fortress. One of the biggest castles in the Mediterranean Sea, the castle grounds span more than 60 acres (0.4 hectares) of land.

Walls of Constantinople

The last major ancient defensive system was the walled city of Constantinople (now known as Istanbul since 1922). They were regularly altered over time, but Theodosius II and Constantine the Great completed the largest buildings in the fourth and fifth centuries, respectively. The walls encircled the whole city, forming a substantial land wall along its western side and a more modest but no less powerful sea wall along its eastern, northern, and southern boundaries. The sea walls, which protected against naval assaults from the Bosphorus and Golden Horn waterways, were less spectacular than the western land walls, and it is sometimes difficult to detect signs of them in contemporary Istanbul.

The western land wall, a gigantic three-tiered system of walls, towers, and moats that was a wonder of military engineering, was built mostly by Theodosius II between 404 and 458 CE. Theodosian Walls are the name given to these walls, which are still substantially standing today. For about 1000 years, they assisted the Byzantine Empire in defending Constantinople from several sieges. After a 7-week siege, the city was finally taken by The Ottoman Empire in 1453 with the use of cannons.

Basilica di San Lorenzo, Milano

In Milan, among the ring of canals, the Basilica of San Lorenzo Maggiore is a significant Catholic shrine that dates back to Roman times and has undergone several reconstructions over the course of several centuries. It is one of Milan’s oldest churches and is adjacent to the ancient Ticino gate. It is next to the municipal park known as Basilicas Park, which houses the Roman Colonne di San Lorenzo as well as the Basilicas of San Lorenzo and Sant’Eustorgio.

Basilica of San Vitale

One of the most significant pieces of early Christian Byzantine art and architecture in Western Europe is the Basilica of San Vitale, a church in Ravenna, Italy. Although it does not have a basilica-like architectural form, the structure is patterned after a “ecclesiastical basilica” in the Roman Catholic Church. It is one of eight Ravenna buildings that have been included on the World Heritage List by UNESCO.

Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe

Near Ravenna, Italy, the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe is a significant piece of Byzantine architecture. This basilica was described as “an outstanding example of the early Christian basilica in its purity and simplicity of its design and use of space and in the sumptuous nature of its decoration” when UNESCO inscribed eight Ravenna buildings on the World Heritage List.

Domestic Architecture

Domestic Byzantine architecture appears to adhere to long-standing customs from the early Roman Empire. It is unknown where the impoverished people live, which is likely in hovels and farms. Our understanding of middle-class homes is more extensive, but it is still restricted to a small number of homes and businesses that have been unearthed in a few Greek cities. We have important specimens from several 12th-century homes discovered during excavations on the Athenian Agora. These buildings are identical to those constructed on the Agora in the fifth century, in Dura Europos in the second century, and in Delos and Priene in the first century.

An Athens city home was generally square in shape, with a courtyard serving as a source of fresh air and light in the middle. Simpler houses with two or three rectangular rooms have been discovered at Corinth. Some of the more sophisticated homes had additional levels, but the small rooms and disorganized floor plans are what set them apart.

Byzantine Fortifications

The land walls of Constantinople, which were constructed in several stages, are an outstanding example of Byzantine city fortification. The main wall is 16 feet broad, 30 feet tall, and four miles long. It is also preceded by a 60-foot-wide moat and another wall. Six gates were utilized to access the city from the main wall’s 96 towers. This was possibly the first instance of the double enceinte being utilized in the Middle Ages.

This fortification system played a significant role in Western Europe’s military history throughout the later Middle Ages. The Sea Walls, the Walls of Blachernai, the Golden Gate, and the so-called Marble Tower are other examples of Byzantine walls that still stand today. After the sixth century, the large-scale fortress construction campaigns tapered off. Defenses were made up of isolated forts and little fortified towns on the eastern boundaries of the Empire, which took the brunt of Byzantine history’s blows.

Ankara Castle

Ankara, the current capital of Turkey, is home to the sizable hilltop stronghold known as Ankara Castle. Ankara Castle is located in the center of the ancient city, on top of a high hill that afforded vistas to all of the surrounding districts, although the exact period of its initial construction is uncertain, many historians think it was during the time of Emperor Constans II. The castle was erected by the Byzantines to assist safeguard the eastern borders of their empire, and it is a classic example of military building from the era. A popular tourist destination nowadays in Ankara’s otherwise contemporary metropolis is the city’s castle.

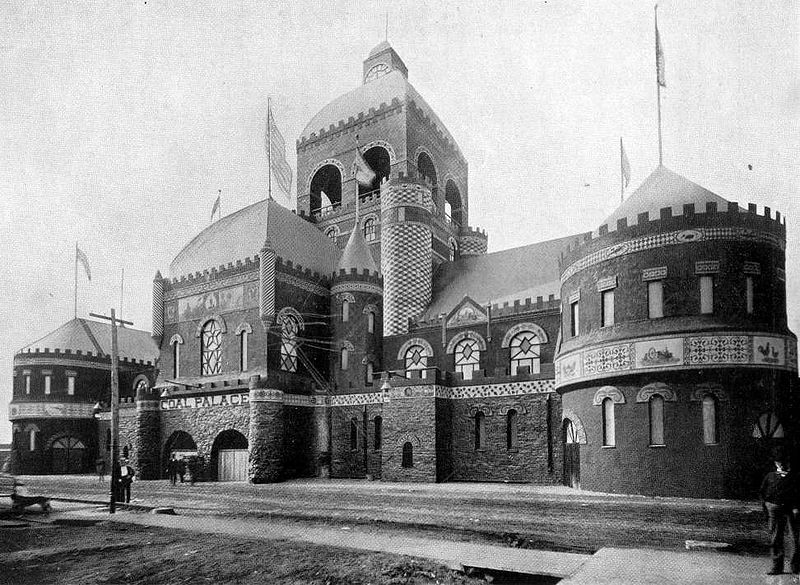

Coal Palace

In Ottumwa, Iowa, The Coal Palace served as a temporary exhibition space from 1890 to 1892. It was primarily utilized to highlight the nearby coal mining sector. President Benjamin Harrison and Congressman William McKinley paid the structure a visit during its brief existence, but the building’s demolition in 1892 was eventually caused by a drop in attendance and the effects of nature on its façade.

The Towers of Byzantium

Towers constructed all around the Empire are fascinating examples of Byzantine defenses. Written sources describe an intriguing set of tower-based Byzantine defensive fortifications arranged in a beacon system. Between Constantinople and Asia Minor’s eastern frontier, this beacon system was utilized for communication. Smoke signals were used by these towers to send messages from one station to the next. According to the sources, it took an hour to deliver the word from the first station to the last. Nine stops from the eastern border are mentioned in the sources: Lulon, Mount Argaios, Isamos, Aigilon, Mount Mamas, Mount Kyrizos, Mount Mokilos, Mount Saint Auksentius, and Faros.

Other stations were perched on hills and mountains, except the first and last stations. North of Taurus, Lulon served as an important frontier fortification. The last station was Faros, the Constantinople lighthouse that was modeled after the lighthouse in Alexandria. Only the first two and the last are still visible today.

The Heptapyrgion and Walls of Thessaloniki

A major city in the Byzantine Empire was Thessaloniki. It had a significant harbor and a strong defense system that rivaled Constantinople, the Byzantine capital. Around 390 CE, under Theodosius I’s rule, the majority of these fortifications were constructed. Many of the walls have been altered and added to throughout the years. Thessaloniki had an Acropolis, just like many other Greek towns. One of the highest locations inside the municipal boundaries is where Thessaloniki’s Acropolis. Starting at the Heptapyrgion, the walls extended all the way to the bay below. The city’s main defensive fortress was a castle-like building called the Heptapyrgion. The Heptapyrgion was later enlarged and ultimately turned into a jail while Thessaloniki was ruled by the Ottoman Empire.

Cadogan Hall

In the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea in Chelsea/Belgravia, London, the United Kingdom, Cadogan Hall is a performance venue with 950 seats. The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the first London orchestra to have a permanent home, is the musical ensemble in residence in Cadogan Hall. In late 2001, Cadogan Estates made the hall available to the RPO for use as its primary location. In November 2004, the RPO performed for the first time in Cadogan Hall as the resident group. One of the two primary London locations for the Orpheus Sinfonia, Cadogan Hall also hosts chamber music performances by The Proms on Saturday mornings and Monday lunchtimes since 2005. Cadogan Hall has been used as a location for recordings in the past. A recording of Mozart symphonies featuring John Eliot Gardiner and the English Baroque Soloists was created in February 2006 and made accessible right away. There, in 2009, the art rock band Marillion captured a performance that was later included on the 2011 CD Live at Cadogan.

Karaman Castle

In Karaman, Turkey, there is a sizable medieval castle fortress known as Karaman Castle. The castle’s initial construction date is uncertain, although historians think it was erected over a considerable amount of time during the 11th and 12th centuries. The innermost of the castle’s three concentric circles of walls was the highest and strongest. When the Seljuk Turks took Karaman in the late 12th century, the Byzantines fled back toward their capital, Constantinople. The Castle is now a well-liked tourist attraction in Karaman, and the area inside the walls is a public park.

Conclusion

There are many examples of Byzantine architecture in the modern world. The triumph of the Byzantine Empire and the buildings it left behind would not have been possible, and contemporary architecture would be quite different today. Whether you consider the Byzantines to be Romans or something else, they were a remarkable culture that changed architecture.